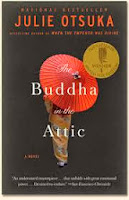

Title: The Buddha in the Attic

Author: Julie Otsuka

Genre: Novel

Published: 2011

Julie Otsuka's book is written in the first person plural - a style I have never seen used before. It was at first distracting as I thought it was simply a foreword and the style would change. Not the case. By the time I was into the second chapter I had started imagining the women in the story as a collective.

The Buddha in the Attic traces the story of Japanese women that make their journey from Japan to San Francisco as picture brides in the early 1900s. She starts off with the first section catchingly- titled, Come, Japanese!

The books opens with a quietly steady chapter that begins:

On the boat we were mostly virgins. We had long black hair and flat white feet and we were not very tall. Some of us had eaten nothing but rice gruel as young girls and had slightly bowed legs, and some of us were only fourteen years old and were still young girls ourselves.

Some of us came from the city,...some of us came from the mountains...

And so it goes. She carefully and steadily crafts the book taking the reader from the boats carrying these women - clutching faded photographs of their husbands-to-be, and excitedly testing the sounds of their foreign names on their tongues- to their new lives in America. Their anxieties about what awaits them on the other side of the ocean; whether or not they will like their husbands; whether their husbands will like them; what their first nights as brides will be like and so on is told collectively and evocatively.

Otsuka's phrases are brief, and detailed all at once as she describes the women's journey on the ship taking them to their new lives in America; the realisation that they were brought to America to be wives of Japanese men employed as farm workers and in a myriad other menial jobs in San Francisco; the disappointment of learning that they have merely traded in their hard lives in Japan for even harder lives as fruits-pickers and maids in America; and finally their acceptance of their respective situations.

They go on to have children, and raise them in a culture that is wholly foreign and in a language that many never fully manage to speak well. They watch as their children grow and slowly begin to turn their backs on their language and culture - giving meaning to the aptly named Buddha in the Attic. Religious practices, traditional customs are reluctantly closeted as their children become more American.

One by one all the words we had taught them began to disappear from their heads. They forgot the names of the flowers in Japanese. They forgot the names of the colours. They forgot the names of the fox god and the thunder god and the god of poverty, whom we could never escape...

They forgot how to pray. They spent their days now living in the new language, whose twenty-six letter still eluded us even though we had been in America for years... They gave themselves new names we had not chosen for them and could barely pronounce.

The latter sections of the book goes into the confusion and pain that these women go through as their lives and families are torn apart in the days preceding their internment. This was a part of American history I did not know fully about, and have since gone on to educate myself on.

The author continues to tell the story from the same perspective, describing the confusion that beset the many Japanese communities as the notices of their impending removal went up on notice boards, the misunderstanding of why and for how long they would be gone for, and ultimately the realisation - for some - that they would not be returning to their homes. The families, which by this time were now fully integrated into society, raising their children, working and running their businesses have to literally pack up their bags and leave it all behind, at the orders of the then President Roosevelt.

In the final chapter titled A Disappearance, the author suddenly changes the narrative to first person singular, changing the perspective from that of the Japanese women to that of the white Americans left behind.

The Japanese have disappeared from our town. Their houses are boarded up and empty now. The mailboxes have begun to overflow. Unclaimed newspapers litter their sagging front porches and gardens. Abandoned cars sit in their driveways. Thick knotty weeds are sprouting up through their lawns. In their backyards the tulips are wilting. Stray cats wander. Last loads of laundry still cling to the line. In one of their kitchens - Emi Saito's - a black telephone rings and rings.As sudden as the change in voice is, it is highly effective because we learn even more of the impact the sudden disappearance of the Japanese had on the communities they lived in; of the questions of their disappearance that remained to the white Americans left behind - many of which were as equally ignorant to the reasons for the removals; and of the ensuing disappearance from memories as they are quickly forgotten.

This is a really good book, that made me want to read Julie Otsuka's first book, When the Emperor was Divine.

Verdict: Highly recommended.

No comments:

Post a Comment